I mentioned Chief Ayar in my last post. I also mentioned that he is one of the favourite characters that I’ve come across through all of my journeys. Chief Ayar is a unique man, he is sometimes considered strong headed, very opinionated and one might even call him a little cunning.

Two things that matter to Ayar more than anything in the world are his land and his culture. He has needed to possess at least a little of the mentioned qualities in order to hold onto these in the quickly modernizing, changing world which swallows and absorbs everything in its path without waiting.

For Ayar, his land is much more than just land. He believes that the spirit of his people came from it, from the thick forest, mountain rivers, creeks and some of the most fertile soil on the planet. Ayar is of that land and the land is a continuation of him, it’s can’t be separated, like an organ vital to the body.

Ayar realizes that others might want to take his land away. Vanuatu’s infamous land disputes are a testament to that and in order to basically not get screwed, you have to be ready to fight and to protect your land and your rights. Before the fighting was done with weapons, now one must play by the rules of the modern world. Ayar has negotiated with the government to create a law which ensures that his land will never be sold and the only way it can be transferred is from generation to generation, just as it has been for as long as anyone can remember.

Should there be any doubt or dispute in the future, Ayar’s children, who have all been given modern, Western education will be able to stand up for their land. The youngest is studying law, the middle is a director of a trading company, both in Port Villa (Vanuatu’s capital) and the eldest owns a small shop, in a village close to the ancestral land.

It is the eldest son to whom Ayar has entrusted the task of keeping the family history and his tribe’s culture alive. He told me that he once pulled the boy aside and said “You’ve had enough white-man education, now it’s time to learn about kastom (the word used for tradition/culture in Vanuatu).” Ayar taught his son how to beat the traditional, wooden gong, how to dance, how to paint masks, how to prepare ceremonies and sacrifice pigs.

It’s hard to tell whether kastom will indeed stay alive for generations, but the pattern which the culture follows in parts of Vanuatu defies reason, or at least it defies the reasoning of most white-men, as the locals refer to almost all Westerns. On Malekula, the home island of Ayar there were still cases of Cannibalism and tribal warfare until late 60s. Then, as majority of the population was finally converted to Christianity, the natives suddenly turned away from their past and at times even became ashamed of it. The Church did their best to discourage anything that would remind the people of their bygone “savage” ways, calling grade-taking and ceremonial pig killing, which were vital parts of the culture for so long – sinful.

By mid seventies, in South West Bay, the area of Malekula island, where chief Ayar’s ancestral land is, most traces of what once made the smol nambas, the formerly fierce cannibal warriors of the region distinct and unique was almost gone. That is until Ayar, inspired and influenced by the knowledge passed on to him by his father decided to hold a grade-taking ceremony, to kill a pig, to become a chief and to begin the revival of the smol nambas culture in South West Bay.

Fascinatingly, before Ayar decided to become a chief he was already a prominent Church member, which meant that he had close ties to the very institution which tried their best not to revive, but to rid the natives off of their history and culture. This didn’t seem right to Ayar and after the pig killing that made him Chief, he went to the Church to pray. This move was intentional, Ayar wanted to show that Church and kastom could go hand in hand, that they could co-exist. The way Ayar saw it, both were about love, peace and respect for other human beings.

The Presbyterian Church had a different opinion and decided to “discipline” Ayar by keeping him away from Sunday services for three months. Unshaken and still convinced that Church and kastom could and should co-exist, Ayar went up into the hills to build a church there for the few unconverted or (semi-converted) tribes. Once the church was completed he started attending the services in nothing more than a namba (a banana leaf around the private member). This was a big no-no once again, but no one could discipline Ayar up in the hills. Again he wanted to show how Church and culture could co-exist, but to his surprise the mountain natives quickly exchanged their nambas for “white man clothes” and began to move away from their ancient traditions without ever really looking back. Unknowingly and unwillingly chief Ayar pushed the only remaining purely traditional people away from their history and culture.

This story would have a very sad ending, if it were to end this way and in most cases, in most countries, it would have. But let’s get back to what I said about the way that the pattern which the culture follows in Vanuatu makes no sense. Interestingly and strangely enough, Ayar’s pig killing and grade-taking gained a small wave of support among some of the older chiefs. It’s as if he reminded them that what they had was too precious to lose, even if it was considered sinful by the Church, and so began a small revival of the old ways, minus the cannibalism or the warfare.

Today South West Bay, Malekula remains a fascinating destination and the main “draw-card” for the few visitors that ever make it there is undoubtedly the culture, which still stubbornly holds on with its last breath, thanks to people like chief Ayar Randes. The younger generation have also recently caught on to the fact that there’s value in what their ancestors have passed on to them, not only spiritual, but commercial value. The few tourists that do make it to South West Bay are willing to pay to watch traditional dances and ceremonies and as a result new festivals and cultural programs are in the plans.

It’ll be interesting to observe which turn the culture of South West Bay takes in the next couple of decades. Will the youth continue to see the value in their past or will they be seduced to leave the small villages of South West Bay for “greener pastures” in Vanuatu’s capital and commercial centre – Port Villa? Will the traditions remain true to their original intentions or will they continue to exist purely as a form of entertainment or cultural experiences for the visitors? One thing for sure is that Ayar Randes is not very keen on festivals or ceremonies which stray away from the “correct” way of doing things, which don’t follow the tribal law laid out by his distant ancestors. He loves the idea of tourism coming and helping the locals understand the value of their culture, but Ayar won’t take what’s sacred to him and simply make a show of it all. The question is – will it matter when he’s gone? No one knows and perhaps for now, there’s no reason to think too hard about the future, but rather to try and catch the present, what still remains of the past.

Chief Ayar showing some moves from traditional ceremonial dances. Every ceremony has its own distinct dance moves, costumes, masks and gong beats. Here he dances by the remains of his “Nakamal”. The same word used these days for Kava bars was initially used for a chief’s sacred house – a place of great spiritual significance for any village. Chief Ayar’s sacred house was destroyed during a hurricane a couple of years ago and it’s been one of his main goals to rebuild it, the same way that it was before.

If you click on the photo to make it bigger you might also notice that behind Ayar is a pole with a face painted on it. The pole has spiritual value, but what’s perhaps most intriguing about this pole, is the way that one has to obtain a right to paint certain symbols on it. The law that dictates this is like an ancient system of copyright. Each new adopter of a particular symbol/pattern has to pay the original owner/inventor or his descendent with pigs.

Ayar loves walking through the forest (or bush as its called in Vanuatu) which falls on his land. He tells me that he isn’t really happy when he’s in the village. The village is community land, he doesn’t feel home there and so every day he walks through the bush, to feed his soul in a sense. He talks about how much he loves the fresh breeze, the smells of various plants, which he occasionally tears off and rubs against each other to demonstrate (the smell). His three dogs (two pictured here) help him chase off any wild pigs, which like to come and make a mess of his crops.

The last time I saw a person so passionate and proud of what their land produced was back in Belarus, in my grandmother’s countryside house. It’s interesting how ultimately there are all these similarities amongst people regardless of where we travel.

Ayar opened up a couple of coconuts for Tanya and I before he masterfully chopped the top off of his own. This was indeed one of the best tasting, sweetest coconuts I ever tried.

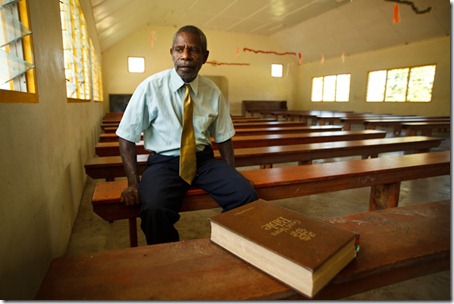

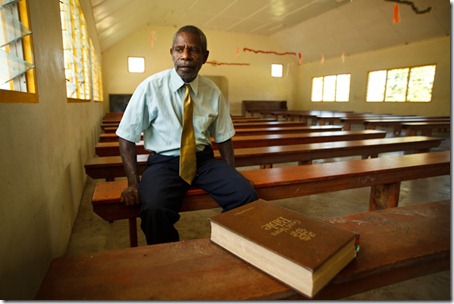

I was pretty shocked when I saw Ayar in this “white-man outfit”. I joked with him, saying that I didn’t recognize him from the man in the namba I had seen a couple of days ago in the bush. To this day Ayar remains closely associated with the Church, in fact he is one of the senior and most respected Church elders in the village of Wintua, which borders with his land. Being what I could describe as a devout non-believer myself (I believe in God, I just don’t believe in names of God or religions) I had a few very interesting conversations with Ayar. At the end of the day it was interesting to know that he’d gladly leave Church and go back to the bush, which is actually what he is planning to do in the next couple of years. When I asked him the pressing question of “What would you chose – Church or kastom?” he replied “kastom – it is my life, my history, my culture.